Writer: Tuana Gamze Kızıltan

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to John Clarke, Michael H. Devoret, and John M. Martins for their experimental demonstration of macroscopic quantum tunneling and energy quantization in electrical circuits.

Their work fundamentally reshaped how physicists think about the scope of quantum mechanics. By directly observing macroscopic quantum tunneling and energy quantization in superconducting circuits, they proved that such quantum effects are not limited to atomic or microscopic systems —they can also occur in macroscopic ones under suitable conditions. This brought a long-standing debate on the scale dependence of quantum behavior to a close.

This discovery was built on nearly half a century of theoretical groundwork. To fully appreciate their achievement, it helps to recall a few key ideas –quantum tunneling, quantization of energy, and decoherence– concepts that define how quantum behavior emerges and fades in the macroscopic world.

Theoretical Foundations: Quantization and Superconductivity

The foundations of quantum mechanics were laid in the early 20th century through the recognition of energy quantization at the atomic level. In simple terms, energy quantization means that physical systems cannot take on just any energy value. Like rungs on a ladder, only specific levels are allowed –electrons, atoms, even circuits must “step” between them rather than move continuously.

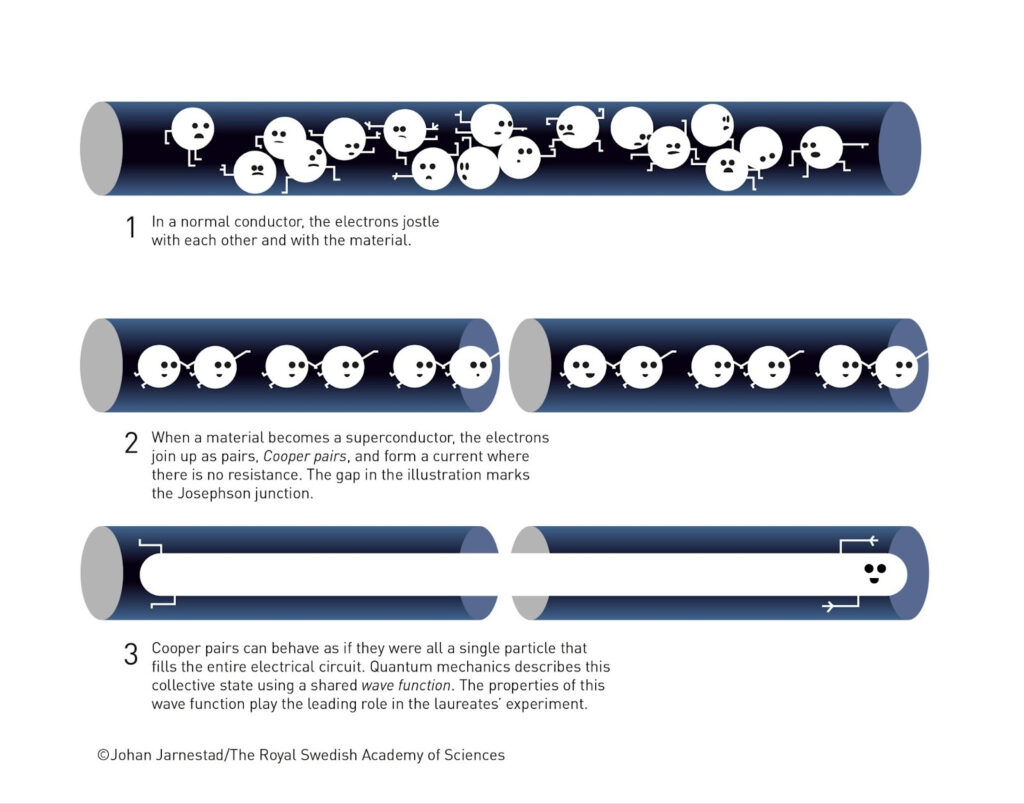

Later studies tried to explain superconductivity within this framework. The Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) theory (1957) proposed that pairs of electrons, known as Cooper pairs, could move collectively without resistance, showing that quantum effects could manifest on a macroscopic scale (Bardeen et al., 1957).

Figure 1. Illustration of how electrons pair up and move coherently in a superconductor. In a normal conductor, electrons scatter and lose energy, whereas in a superconducting state they form Cooper pairs that flow without resistance. The image also depicts a Josephson junction, highlighting the collective behavior described by quantum mechanics. / Credit: Johan Jarnestad / The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Superconductivity can be thought of as a collective quantum motion –a synchronized state where electrons stop behaving as separate particles and instead move as a single, coherent wave through the material. In this state, electrical current flows without resistance, something impossible in the classical world where every motion loses energy to friction. It is one of the clearest demonstrations that quantum order can extend from the microscopic realm of atoms to the macroscopic world of matter itself.

The Josephson Effect: Tunneling Across the Macroscopic Barrier

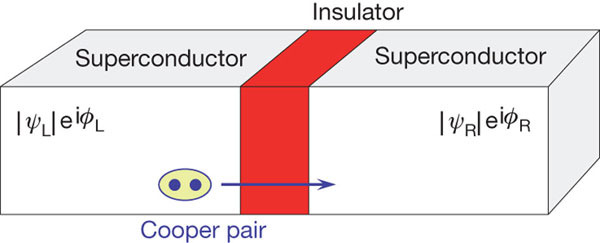

By the late 1950s, findings showed that quantum laws might extend beyond atomic systems. A key theoretical step came from Brian D. Josephson in 1962, who predicted that Cooper pairs could tunnel through a thin insulator between two superconductors (Josephson, 1962).

Figure 2. A Josephson junction, where φ represents the phase. / Credit: You & Nori (2011), “Atomic physics and quantum optics using superconducting circuits,” Nature 474, 589–597. DOI: 10.1038/nature10122

To picture this, imagine two lakes separated by a thin dam. Classically, no water should pass through. But in the quantum case, a coordinated flow can appear across the barrier –not because the dam breaks, but because the wave nature of particles lets a current “tunnel” through. That’s the Josephson effect.

The Josephson effect was soon confirmed experimentally and earned him the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physics. It showed that the quantum phase difference between superconductors could be measured directly –clear proof that quantum laws could govern macroscopic variables. This turned the microscopic picture of BCS theory into experimental reality and opened a new era for studying macroscopic quantum phenomena.

Still, it remained unclear under what physical conditions such macroscopic quantum behavior could persist.

Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition

By the late 1970s, theorists focused on understanding the quantum-to-classical transition. In this context, A. O. Caldeira and A. J. Leggett developed a model that included the interaction between a quantum system and its environment, introducing the concept of decoherence (Caldeira & Leggett, 1981). Their model suggested that no quantum system lives in total isolation. Every interaction –a stray proton, a vibration, a bit of heat– acts like a silent observer, gradually forcing the system to “choose” a definite state. This is how quantum indeterminacy fades into classical certainty.

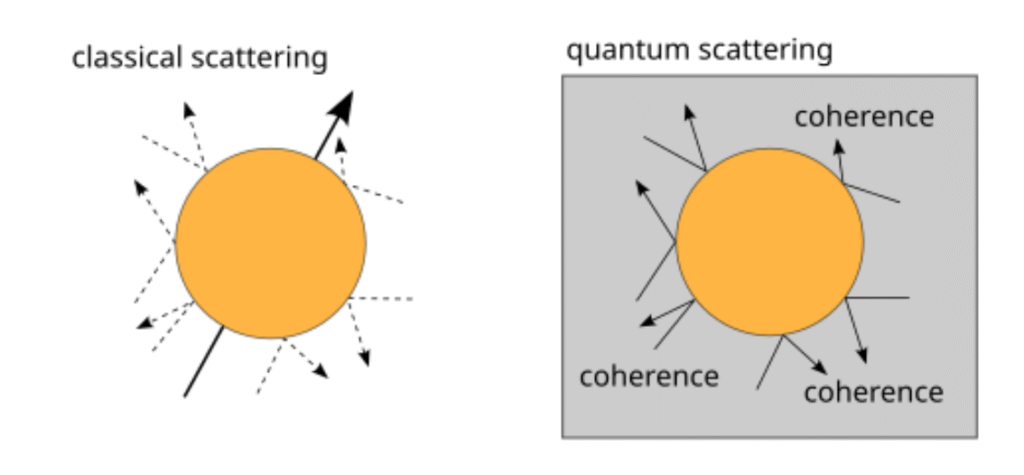

Figure 3. Illustration of classical versus quantum scattering. In classical scattering (left), a particle’s path is independent and random, while in quantum scattering (right), wave-like behavior allows interference and coherence between possible paths. This coherence underlies many quantum phenomena, including decoherence when lost through environmental interaction. / Credit: Maximilian A. Schlosshauer (2007), “Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition.” Springer Science & Business Media. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-540-35775-9

The Caldeira-Leggett model predicted that coherence in macroscopic quantum systems decays rapidly due to environmental noise, thermal effects, and energy loss. In simple terms, decoherence is what happens when a quantum system stops behaving quantum-mechanically because it begins to interact with its surroundings.

When isolated, a quantum system can exist in a superposition –several possible states at once– but as it interacts with the environment through heat, light, or vibrations, this fragile balance breaks down. The system then appears classical, as if only one outcome had ever existed.

This idea provided the first quantitative framework for explaining how classical behavior emerges from quantum laws, highlighting how difficult it is to isolate a pure quantum state at large scales.

Experimental Breakthrough: Macroscopic Quantum Tunneling

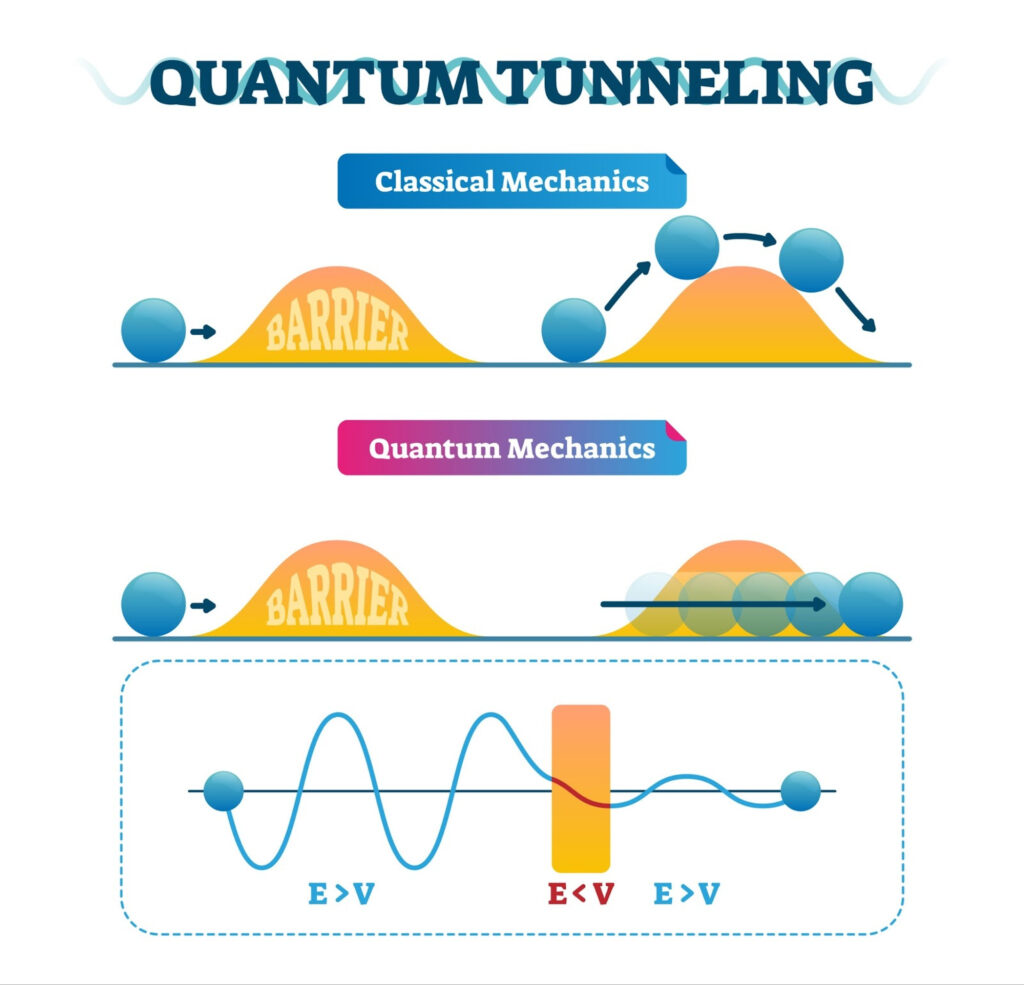

Figure 4. Quantum Tunneling Mechanism. The illustration shows a particle’s wave function (ψ) penetrating an energy barrier even when its kinetic energy (E) is insufficient to overcome it classically. This quantum leakage mechanism was experimentally observed for the macroscopic phase variable in superconducting circuits.

Building on this theoretical foundation, Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis directly tested these concepts in the mid-1980s, providing the first experimental proof of macroscopic quantum tunneling.

Their experiments asked a simple but profound question: could a macroscopic variable –such as the phase of current in a superconducting Josephson circuit– obey quantum mechanics?

In quantum mechanics, tunneling describes how a particle can pass through an energy barrier even if it doesn’t have enough energy to climb over it. Imagine a ball resting in a valley –it shouldn’t be able to roll through the hill beside it, yet in the quantum world, it sometimes does. This happens because particles also behave like waves, giving them a slight but real chance to “leak” through the barrier.

Working at extremely low temperatures, these researchers shaped the potential energy landscape of their circuits to resemble such a quantum well. This made it possible to detect the tunneling of the phase variable between distinct energy levels. The current transitions they observed clearly deviated from classical predictions, showing that the system could escape its zero-voltage state by quantum tunneling. What makes this remarkable is the scale: the variable that tunnels here isn’t a single particle, but a collective property –the phase of current in an entire circuit. The experiment showed that even a macroscopic system could “leak” through its own energy barrier. It was the first direct evidence that a macroscopic variable could behave quantum-mechanically (Devoret et al., 1985; Martinis et al., 1987).

From Discovery to Technology

These studies did more than confirm a theory –they founded the new field of quantum circuit physics (Devoret & Schoelkopf, 2013). The experiments revealed that tunneling rates and energy levels in superconducting circuits followed quantized patterns, transforming superconductivity from a microscopic phenomenon into an engineered quantum system.

The work of Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis experimentally demonstrated that superconducting circuits can sustain stable quantum behavior, redefining the boundary between quantum physics and applied engineering. Their findings laid the groundwork for applications ranging from computation to precision measurement.

What began as an abstract curiosity –the idea that matter behaves like waves– has turned into an engineering principle. Each controlled quantum state is a reminder that understanding is not just seeing nature as it is, but learning how to rebuild it under our own conditions.

Later, their results became the physical basis for qubit architectures –especially flux, phase, and transmon qubits (Devoret & Schoelkopf, 2013). Quantum mechanics thus evolved from a theory describing nature to a tool for building technology that follows its laws.

From the 1990s onward, these techniques shaped modern quantum technologies. Operating superconducting circuits reliably at the quantum level revolutionized quantum information processing and metrology. Different qubit designs offered unique strengths in coherence, error reduction, and control precision.

At Yale University, the transmon qubit was developed to make energy levels more resistant to noise, setting a new standard for long-coherence quantum measurements. This design now underlies platforms such as IBM Quantum and Google Quantum AI, enabling scalable superconducting quantum computers (Arute et al., 2019).

Beyond Computation: Quantum Measurement and Metrology

Clarke’s earlier work also left a lasting mark on measurement science. The Superconducting Quantum Interference Device (SQUID), developed in the 1970s, allowed magnetic flux to be measured in single-quantum units –an early form of quantum sensing (Clarke & Braginski, 2004). Today, SQUID-based systems are widely used in fields from brain imaging (MEG) to geophysics and materials research.

These advances turned the discovery of macroscopic quantum tunneling from a basic confirmation into a practical tool of engineering. Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis not only observed a phenomenon –they built the technological foundations of the quantum era.

Maintaining quantum behavior in macroscopic systems depends on controlling decoherence, the loss of quantum coherence through environmental interaction. In superconducting qubits, magnetic noise, thermal fluctuations, and microwave leakage can all trigger a return to classical behavior, limiting data retention and computational accuracy.

Maintaining quantum behavior in macroscopic systems depends on minimizing decoherence –the loss of quantum coherence through environmental interaction. Controlling such effects remains one of the central challenges in realizing practical quantum technologies.

In the long term, superconducting quantum circuits have potential for beyond computing. They are becoming central to quantum metrology, redefinitions of fundamental constants, and even emerging studies of quantum gravity. The work of Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis helped transform quantum mechanics from a theoretical framework into an applied scientific discipline.

Conclusion: The Quantum Age

This year’s Nobel Prize reminds us that quantum mechanics is no longer just a theory –it has become an engineering language that lets us reproduce the laws of nature in the lab. The experiments of Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis carried “quantum” from the subatomic scale to the laboratory scale, making the boundary between classical and quantum behavior something measurable.

Today’s superconducting qubits, quantum sensors, and fault-tolerant processors are built upon that boundary. By honoring this work, the Nobel Committee highlights the direction of modern physics: testing a theory in the laboratory does not only explain nature –it opens the way to transform it. The experimental proof of macroscopic quantum tunneling marks, in every sense, the true beginning of the quantum age.

References

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. (2025). The Nobel Prize in Physics 2025 – Press Release.https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2025/press-release/

Arute, F., Arya, K., Babbush, R., Bacon, D., Bardin, J. C., Barends, R., … & Martinis, J. M. (2019). Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature, 574(7779), 505–510. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1666-5

Bardeen, J., Cooper, L. N., & Schrieffer, J. R. (1957). Theory of superconductivity. Physical Review, 108(5), 1175–1204. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.108.1175

Caldeira, A. O., & Leggett, A. J. (1981). Influence of dissipation on quantum tunneling in macroscopic systems. Physical Review Letters, 46(4), 211–214. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.46.211

Clarke, J., & Braginski, A. I. (Eds.). (2004). The SQUID handbook: Fundamentals and technology of SQUIDs and SQUID systems. Wiley-VCH.

Devoret, M. H., Martinis, J. M., & Clarke, J. (1985). Measurements of macroscopic quantum tunneling out of the zero-voltage state of a current-biased Josephson junction. Physical Review Letters, 55(18), 1908–1911. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.1908

Devoret, M. H., & Schoelkopf, R. J. (2013). Superconducting circuits for quantum information: An outlook. Science, 339(6124), 1169–1174. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1231930

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M., & Cleland, A. N. (2012). Surface codes: Towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Physical Review A, 86(3), 032324. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.86.032324

He, H., Xiang, Y., Han, Y., Wang, S., & Guo, Y. (2022). Suppressing the dielectric loss in superconducting qubits: Design and experiment. Entropy, 24(7), 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24070952

Josephson, B. D. (1962). Possible new effects in superconductive tunneling. Physics Letters, 1(7), 251–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9163(62)91369-0

Martinis, J. M., Devoret, M. H., & Clarke, J. (1987). Experimental tests for the quantum behavior of a macroscopic degree of freedom: The phase difference across a Josephson junction. Physical Review B, 35(10), 4682–4698. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.35.4682

Roffe, J. (2019). Quantum error correction: an introductory guide. Contemporary Physics, 60(3), 226–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107514.2019.1667078

Schreier, J. A., Houck, A. A., Koch, J., Schuster, D. I., Johnson, B. R., Chow, J. M., … Devoret, M. H. (2008). Suppressing charge-noise decoherence in superconducting charge qubits. Physical Review B, 77(18), 180502. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.77.180502