Writer: Tuana Gamze Kızıltan

1. Introduction

Research papers are the most current, reliable, and systematic source of scientific knowledge. Although textbooks contribute to our academic and professional lives by teaching us the fundamental concepts and providing a general framework, it is also necessary to deepen and broaden this knowledge. Science is constantly developing, and the most recent, peer-reviewed, and open-to-discussion products of this advancement are found in research papers.

For students and early-career researchers, reading papers is not only a way to acquire knowledge but also a process that transforms one’s way of thinking. In courses or popular science sources, we often encounter “ready-made knowledge”, but when we read research papers, we see how knowledge is produced, what questions it seeks to answer, and what methods are used to test it. This experience takes us beyond being passive “consumers of knowledge” and helps us become individuals who can think critically, question methods and results, and develop our own research questions. In brief, learning to read research papers is the first step toward becoming an active participant in the scientific world rather than an observer. However, for many students, their first encounter with academic articles is not easy. Long and complicated sections of methods, dense terminology, or complex statistical analyses can make these texts seem hard to read and incomprehensible. They may even create the impression that reading papers is an endeavour reserved only for experts in the field. Yet this perception does not reflect reality.

Reading research papers is a skill that can be learned; when approached systematically, accessing the information contained in an article is much easier than it seems. Moreover, this process contributes to the development of scientific reasoning and critical evaluation skills beyond simply understanding the findings. The purpose of this article is to change our perspective on academic articles, provide tips to make them easier to understand, and make the reading of articles more efficient for students through systematic reading methods.

Identifying the article type, recognizing its structure, and approaching it with a systematic strategy are among the most effective tips to make the reading process easier and more efficient.

The first step in reading an article effectively is to determine what type of article it is.

2. Types of Research Papers

The purpose of research papers can not be limited to only presenting data. Besides, every paper does not need to be written with the same purpose. Various types of research papers serve different scientific purposes, differing in terms of method, argument, conclusion, and the way in which these are presented. Therefore, attempting to read an article without knowing its type can lead to confusion.

The primary types of research papers include empirical, theoretical, and methodological papers:

2.1 Empirical Papers:

Empirical papers are the most common type, which collect data within the framework of a specific research question, analyse the data, and draw conclusions based on the findings. Experimental biology, clinical studies, or field research in the social sciences are typical examples. This type of paper focuses on the data generated through observation and experimentation.

2.2. Theoretical Papers:

Theoretical papers do not produce new data directly. Instead, they develop conceptual frameworks, reinterpret existing knowledge, establish connections between different approaches, or propose new models. An evolutionary modelling approach in biology or a critical analysis of existing theories in psychology are some examples of theoretical papers. They aim to expand the intellectual basis of the field.

2.3 Methodological Papers:

Rather than establishing theories or presenting new data, these papers focus on developing research methods or introducing new techniques, tools, or approaches, thereby opening new pathways for researchers. For instance, the development of a new imaging or measurement technique in molecular biology, improvements to laboratory protocols, or a novel survey design in the social sciences are all categorised under the methodological papers.

In addition to these three main types, other formats also appear in academic publishing: reviews, case reports, editorials, short technical notes, or commentaries. The purpose of these types, which meet different needs of the literature, is mostly to provide a general overview of a specific topic or to discuss existing studies.

Knowing the type of a research paper is crucial for determining a suitable reading strategy. For an empirical paper, one must focus on the methods and results sections, whereas for a theoretical paper, the emphasis should be placed on conceptual arguments and discussions.

Once we have identified the type of paper, the next question arises: What does the aim of the paper tell us, and in what order? To read a research article effectively, it is not enough to know its type; we must also understand its structure. Therefore, the next step is to take a closer look at the main sections of the paper and understand what each section is about.

3. The Anatomy of a Research Paper

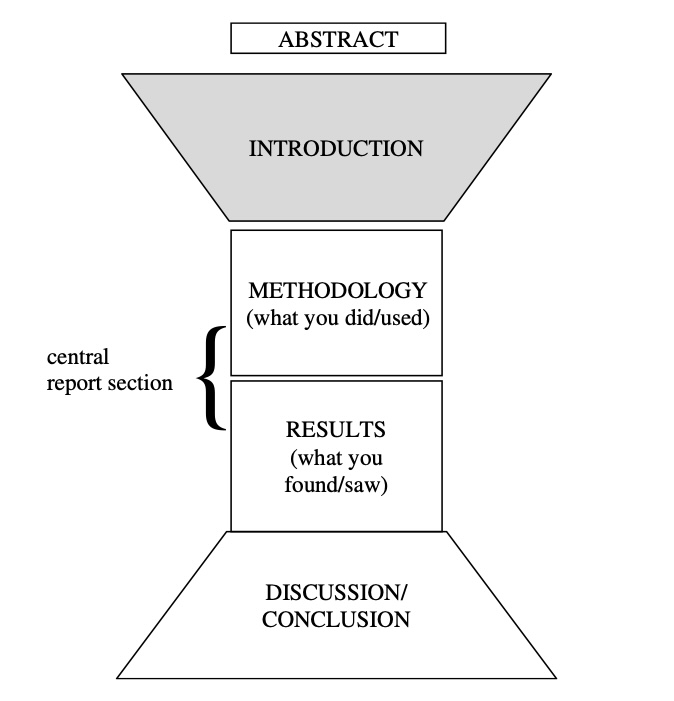

A research paper follows a particular structure that makes it easier for readers to follow the text. Knowing this structure makes it easier to understand the article by breaking it down into parts rather than reading it from beginning to end as a single, uninterrupted whole.

3.1 Title:

Reflects the subject of the study in the shortest way possible and gives an immediate idea of the field to which the paper belongs.

3.2 Abstract:

Briefly explains the aim, methodology, main findings, and conclusion of the study in a few sentences. This section is often the most useful part for deciding whether to continue reading the paper or not.

3.3 Introduction:

Presents the general context of the topic; explains which research question is being investigated and why it is important. It also refers to previous studies and indicates the gaps in the current literature that the study aims to fill.

3.4 Methods:

This section describes how the research was conducted. This includes the experiments performed, how data were collected, and which materials, tools, or statistical techniques were used. The methods section is the key reference point for evaluating the reliability of a study.

3.5 Results:

The data obtained as a result of the research are presented in this section, supported by tables, graphs, and figures. The results show the findings without interpretation; the meaning of the data is explained in the next section.

3.6. Discussion / Conclusion:

This section examines the significance of the findings. The author compares the results with other studies in the literature, discusses their strengths and limitations, and points to possible questions for future research.

3.7. References:

This is a list of previous studies that the author relied on in constructing the article. The references are referred to within the text. For readers, it is an important guide for further reading on the topic.

3.8. Supplementary Data:

Contains detailed experimental information, tables, or additional analyses that were not included in the main text. In natural sciences, this section is often quite extensive.

However, even if we know which sections a research article consists of, effective reading is not limited to simply recognising these sections. What truly matters is knowing how and in what order to approach these sections. This is where reading strategies become crucial.

4. Reading Strategies

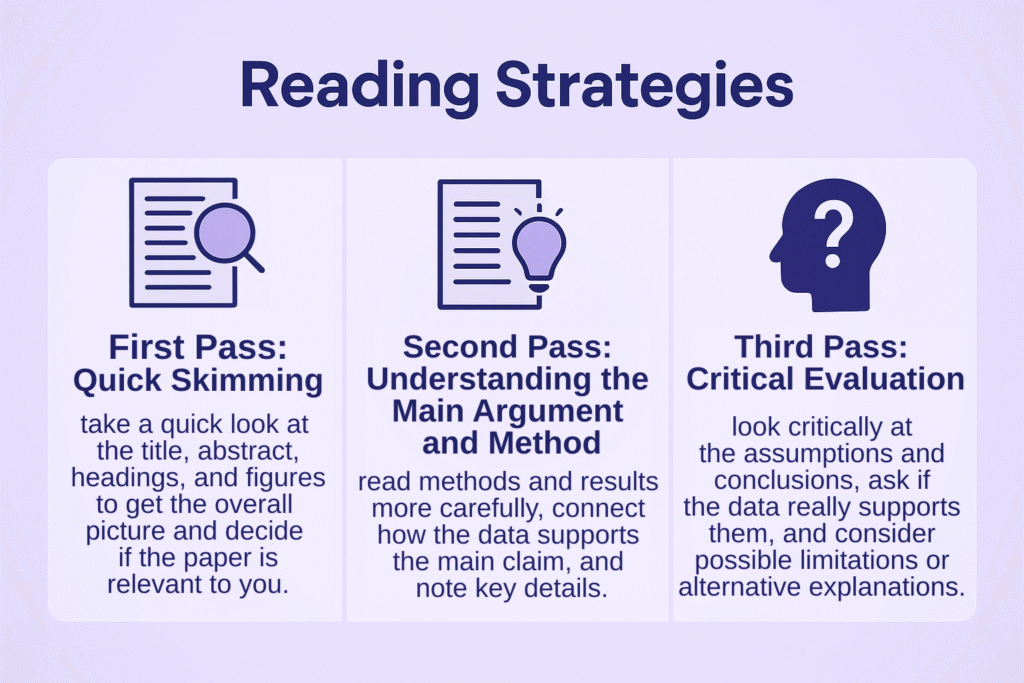

Reading a research paper effectively involves much more than simply following every sentence line by line. Reading from beginning to end can often be tiring and inefficient. Instead, a systematic reading approach allows both efficient use of time and deeper engagement with the text. Srinivasan Keshav’s “three-pass reading” method offers a highly functional roadmap in this regard. In this method, three main passes are suggested.

Fırst Pass: Quıck Skımmıng

The first pass aims to grasp the overall framework of the article without delving into the details. This stage usually takes 5–10 minutes and allows the reader to determine whether the text captures your attention. The title, abstract, and first part of the introduction should be read carefully; section headings and subheadings should be skimmed. Figure and table titles are particularly important, as they often reveal the research question and methodology directly. In the natural sciences, figures are the backbone of the paper; the experimental approach and key trends are usually understood through visuals. Glancing at the key sentences in the conclusion also helps clarify the author’s takeaways. Briefly scanning the reference list can also be useful to see if there are any studies we are already familiar with.

This pass allows the reader to address five essential questions (5C): What is the paper’s category? In what context was it written, and on what studies is it based? Do the assumptions seem correct? What are its main contributions? And most importantly, is the style of expression clear and understandable? After this first pass, the reader should be able to answer the question, “Is this paper truly relevant for me, and is it worth reading in detail?”

Second Pass: Understandıng the Maın Argument and Method

If the paper seems relevant, the second pass focuses on understanding the author’s claim and how it is supported by methodology. This stage usually takes about an hour. The introduction, methods, and results sections should be read carefully; unfamiliar terms should be noted and, if necessary, looked up immediately. One of the most critical points here is to establish the connection between the methods and results. While reading the results section, one should constantly ask: “Which experiment, measurement, or analysis does this result come from?” Method-result matches make it easier for us to see the origin of the data and provide a basis for questioning the reliability of the findings.

In addition, close attention should be paid to visuals in this pass. Are axes in graphs correctly defined? Are error bars provided? Is statistical significance indicated? Such details provide key insights into the reliability of the study. Taking notes increases the efficiency of this stage: summary sentences, concept lists, or highlights save considerable time when we return to the same paper later.

By the end of the second pass, we should be able to summarise the main points of the paper to someone else: What is the author arguing, which methods are used, and what findings are reported? Full comprehension of all details may not yet be achieved, but the main argument should be clear.

Thırd Pass: Crıtıcal Evaluatıon

The third pass is the most challenging but also the most instructive stage of reading a research paper. The aim here is not just to understand but to critically evaluate the work and reconstruct it in our minds. The author’s assumptions are questioned one by one, and the methods used are reimagined in our minds. We carefully examine whether the findings truly support the author’s conclusions, whether alternative explanations are possible, and what the methodological limitations are.

At this stage, the reader becomes an active inquirer. The question, “If I were conducting this study, what approach would I take? If I had these data, how would I interpret them?” is one of the most powerful tools of critical thinking. Students often hesitate to criticise because of a lack of knowledge, at this point. However, critical evaluation is not about proving the author wrong; it is about developing one’s own reasoning skills. Perfect critiques are not expected; what matters is avoiding blind acceptance and testing alternative perspectives. This skill does not develop in a day; it requires time and repeated practice.

Reading strategies thus enable us to interact more effectively with scientific texts. Still, it is quite natural and common to make mistakes when trying to apply these strategies, especially in the early stages. Recognising these mistakes is an important step in both improving our reading practice and advancing our critical thinking skills.

5. Common Mistakes

When learning to read research papers, students often make similar mistakes (as we mentioned earlier, these are naturally expected). Relying solely on the abstract, jumping directly to conclusions without examining the data, accepting the author’s conclusions without questioning them, overlooking figures, avoiding unfamiliar concepts, expecting to understand everything in a single reading, and feeling inadequate are the main causes of these mistakes.

The first of these mistakes is relying solely on the abstract. The abstract provides a general idea about the study but does not reflect the details of the methodology, the limitations of the findings, or the depth of the discussion. Therefore, trying to understand the text by reading only the abstract can easily lead to a misinterpretation of the paper.

Another common mistake is jumping directly to the conclusion without considering the data. Accepting the author’s claims without examining the results eliminates the opportunity to question the logical consistency of the study. This often stems from the anxiety of “I need to finish this quickly” or from approaching paper reading as only an assignment.

Similarly, uncritically accepting the author’s conclusions is also common. Inexperienced readers, in particular, may evaluate the author’s conclusions without hesitation about themselves. Yet critical evaluation is far more than proving the author wrong; it is a highly valuable way to strengthen our own independent and questioning thinking skills.

Neglecting visuals and figures while reading articles is also a significant shortcoming. Graphs, tables, and figures are often the most information-dense parts of a research paper. Ignoring them creates a non-fluent and incomplete reading experience.

It is also common for readers to stop reading an article when encountering unfamiliar concepts. At such moments, the thought “I don’t understand, so it must not be for me” may prevail. However, taking notes on unfamiliar terms and seeking help from dictionaries or additional sources when needed is a natural and necessary part of the learning process.

Another misleading expectation is to understand everything in a single reading. In reality, this is rarely possible. Reading research papers is a cumulative process, and in most cases, revisiting a text or consulting multiple papers on the same subject proves to be the most effective strategy for deeper understanding.

Finally, many students feel inadequate when faced with complex terminology, detailed experiments, or advanced analyses. This feeling is typically rooted not in the difficulty of the text but in the reader’s own expectations. Reading research papers is a skill that improves with practice, and struggling at first is one of the most natural stages of the process.

Overcoming these common mistakes may be more achievable than it may seem. Developing effective reading habits and making use of supportive digital tools can significantly strengthen our engagement with scientific texts. Thus, reading articles not only becomes a more efficient process but also a sustainable learning practice.

6. Recommendations and Tools

Reading research papers is not only an individual skill, but also a process that can be enhanced through supportive habits, tools, and activities. First of all, using digital tools for source management and note-taking provides great convenience. Software such as Zotero and Mendeley allows users to archive articles in an organised manner, store references accurately, and add annotations. Platforms like Notion can be used to create concept maps, categorise reading notes, and establish connections between different sources.

Systematising note-taking methods also improves efficiency. For instance, the Cornell note-taking system enables recording concepts, main ideas, and personal questions separately during reading. Similarly, techniques such as the “explain in your own words” approach or the Feynman method reinforce comprehension, since re-expressing knowledge is a sign of truly understanding it.

Beyond individual study, journal clubs or reading groups also provide an important learning environment. Such activities bring together different perspectives and help keep critical thinking alive. Techniques such as the “explain in your own words” approach, or called the Feynman method, reinforce comprehension, since re-expressing knowledge is a sign of truly understanding it.

Finally, it should not be forgotten that AI-powered tools can also be helpful in this process. Such tools can be useful, especially for quickly explaining unfamiliar concepts or interpreting tables and graphs. However, it is important to note that these tools should not replace the article itself but rather be used as an additional resource to support the reading process.

7. Conclusion

Reading academic articles may seem challenging at first, but it is a skill that can be developed over time. As we learn to distinguish between types of papers, recognise their structure, and apply systematic reading strategies, the process becomes more efficient, productive and comprehensible. The digital tools, note-taking techniques, and collaborative reading practices used in this journey also help the students’ understanding and make learning more sustainable.

Learning to read research papers holds significance beyond simply succeeding in classes or research projects. At the core of science lies inquiry, evaluating methods, and interpreting data rather than memorising. Therefore, reading articles is a fundamental step in becoming a true part of the scientific community as a student or researcher.

Ultimately, consistent practice in reading research papers strengthens not only academic success but also critical thinking, analytical questioning, and lifelong learning skills. Texts that initially seem complex and unfamiliar gradually become more accessible; over time, reading research papers transforms into a natural and indispensable part of the scientific thinking journey.

8. References

Aliotta, M. (2018). Mastering academic writing in the sciences: A step-by-step guide. CRC Press.

Carey, M. A., Steiner, K. L., & Petri, W. A. (2020). Ten simple rules for reading a scientific paper. PLoS Computational Biology, 16(7), e1008032.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008032

Edwards, P. N. (2014). How to read a book (Version 5.0). University of Michigan, School of Information.

https://pne.people.si.umich.edu/PDF/howtoread.pdf

Keshav, S. (2007). How to read a paper. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review, 37(3), 83-84.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1273445.1273458

MIT OpenCourseWare. (2012). Tips on reading research articles critically and writing your critical response papers.

Purugganan, M., & Hewitt, J. (2004). How to read a scientific article. Rice University, Cain Project in Engineering and Professional Communication.

http://www.owlnet.rice.edu/~cainproj/courses/HowToReadSciArticle.pdf